1. Data Engineer

2. Data Visualisation Specialist

3. Big Data Architect

- Marketing and analytical skills

- RDMSs (Relational Database Management Systems) or Foundational database skills

- NoSQL, Cloud Computing, and MapReduce

- Skills in statistics and applied math

- Data Visualisation, Data Mining, Data Analysis and Data Migration experience

- Data Governance (an understanding of the interaction between Big Data and Security)

|

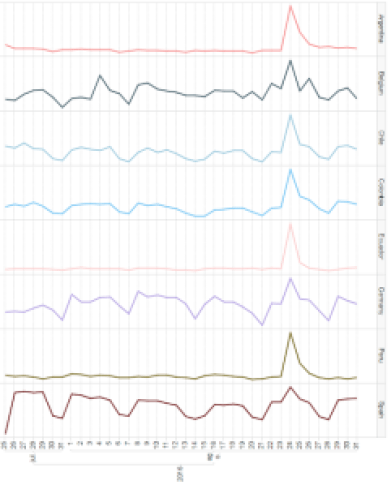

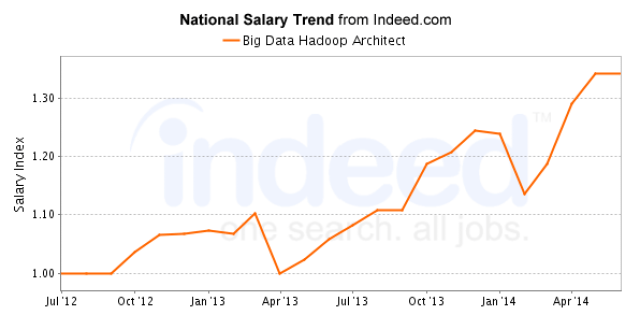

| Figure 2: US Salary Trend for Big Data Hadoop Architect |