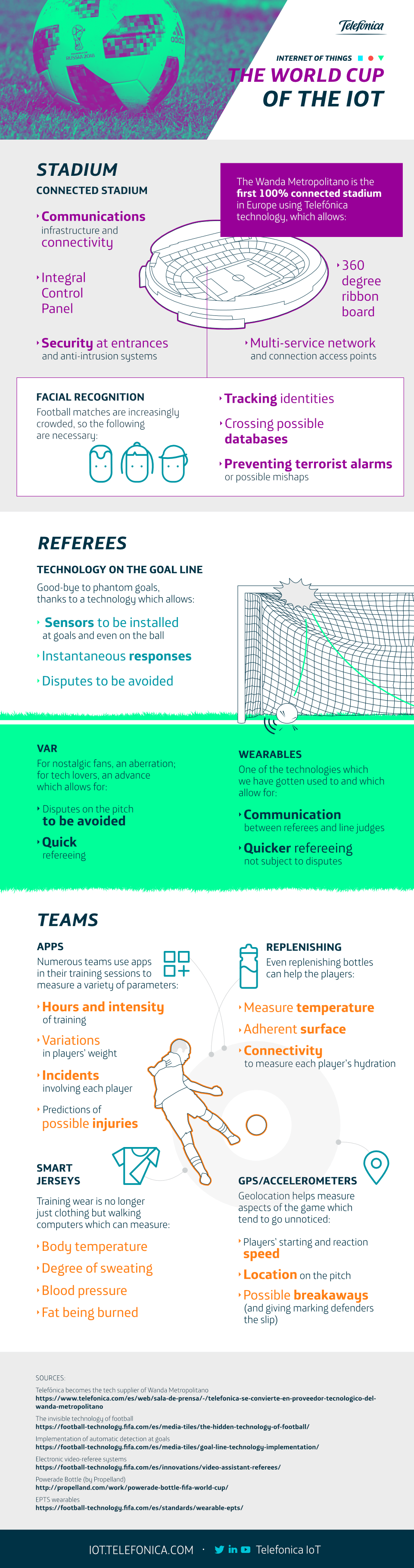

The connected technological solutions are being applied in the football industry, with features such as facial recognition, smart stadiums, connected clothes, statistics tracing apps, wearables or sensors for the detection of goals.

The connected technological solutions are being applied in the football industry, with features such as facial recognition, smart stadiums, connected clothes, statistics tracing apps, wearables or sensors for the detection of goals.

On the 11th April 1945, just two days before his death, during the celebrations of Jefferson Day, Franklin D. Roosevelt uttered a phrase that would remain forever in history: “with great power comes great responsibility”.

As strange as it may sound, many people (including the youth of today) don’t relate this quote to the American president, but with another character from the same country, Uncle Ben. He is Spiderman´s uncle, who uses the phrase in one of the films from the saga. This anecdote, although simple, helps us to emphasize that people do not always know how things are in reality, nor how they come to us. Hence, another famous phrase that says: “I am responsible for what I say, not for what you understand. ¨

However, in the business environment, maintaining an attitude in this regard could be a serious mistake, because it is essential for companies to ensure that the messages they transmit arrive clearly, and without delay, to the recipients. And when we talk about messages, it is not just direct messages, but also the image they are projecting with their actions.

One of the areas which has just begun to have a special relevance is the way in which companies make use of big data. Society is beginning to understand the power that data provides and, consequently, is beginning to demand responsibilities to the same extent.

As a recent example of this, we can remember the scandal that Facebook has had to face as a result of the mis-use of user data by Cambridge Analytica. In case you do not know the case, during the spring of 2018, it was discovered that users of the social network received personalized information on its walls with the aim of influencing their political position. This information was customized with the purpose of being as effective as possible and was based on the knowledge that the social network had about each of its users; forcing its founder to have to appear before the United States Senate and before the European Parliament.

As a consequence of this and other scandals, society is claiming limits to the enormous power that data confers to large companies. In this sense, we can refer to the restrictions that have been established in European data protection regulations in relation to decisions based only on automated means or, similarly, that individuals are subject to decisions taken by an algorithm. The most used example to illustrate this type of decision is the process of assessing the financial capacity of an individual when applying for a loan. If the bank denies this request based solely on an automated decision, citizens have the right to express their opinion or challenge the decision and even request the participation of a person in the process. This is a very important limitation because, otherwise, individual injustices based on collective data could occur, let’s not forget, that the decision made by the algorithm is not based solely on our information, but on that of other people with profiles similar to ours.

I remember some time ago I had a very interesting conversation on this subject, in which my interlocutor commented that, thanks to algorithms, the decisions that were made today were fairer, because it eliminated the danger of being influenced by the prejudices that we as humans sometimes have. Basically, he argued that the algorithms, unlike people, could not be accused of discriminating. And at times this is true and sometimes it is not.

Algorithms discriminate. Of course, they do. In fact, it is one of its main practical applications in the field of Big Data. The difference with humans lies in the fact that the algorithms discriminate in an objective way (based on data), while humans do it in a subjective way (based on experiences, tastes or beliefs). Thus, it is expressed that nothing can be blamed on algorithms about their decisions, because they are “pure.” However, it is a complicated topic. In my opinion, the only real way to avoid discrimination based on certain critical aspects (gender, race, etc.) is to completely eliminate this information from the training and decision data sets of the algorithms. Although, in reality, even that is not enough, since many of these aspects can be inferred through the combination of other data.

Another area in which special focus must be placed is to avoid influencing the digital divide, which, in its most extreme cases, leads to digital poverty. The digital divide defines the inequalities that occur as a result of differences in access to technology, whether for economic reasons (scarcity of resources to acquire devices or connect to the network), knowledge (people of advanced age or with little intellectual training that prevents them from being users of a specific technology) or even for reasons of personal attitude (people who voluntarily choose not to live connected).

Economic actors and Public Administrations have a moral duty to combat the digital divide. The creation of analogue ghettos should be avoided at all costs, those in which the users who conform them have fewer benefits or opportunities due to the fact that they are less attractive to companies or that it is more difficult for administrations to provide them with public services. And, in the same way, mechanisms must be provided that allow a dignified life to be lived for all those who, as conscientious objectors, choose not to be digital individuals. The tricky part of this issue is how to achieve these objectives without affecting the overall progress of the rest of society. An example that shows that these are not future issues but totally current, is the debate that exists today in Sweden about the elimination of physical money, in favour of digital means of payment. There are voices that have begun to expose the significant damage that this measure would mean for certain groups.

For all that has been mentioned so far and for many other examples that do not fit into a single article, we all, as a society, do the right thing by demanding those who have the power of Big Data to honour their responsibility to us.

Telefónica, as a digital leader in Spain and Latin America, has taken good note of this. The main test is the impulse that, from the president of the company, is being made for the creation of a new digital compact. In the manifesto published in favour of said pact, the company ensures that “a digitalization focused on people must ensure that citizens are its main beneficiaries and feel in control.”

The mere fact of having published a manifesto on these issues highlights the commitment of the Telefónica group. However, this commitment is not limited only to making proposals and inviting change, but preaches by example, through concrete measures such as, for example, the fact of having a specific area of “Big Data 4 Social Good” led by Pedro Antonio de Alarcón; whose objective is to use Telefónica’s internal data, together with other external data, to return the value of the data to the world, thus contributing to the Sustainable Development goals set by the UN by 2030. In the same way, the Digital Transformation Area of Fundación Telefónica, directed by Lucila Ballarino, seeks to combine technology with social action and has its own Big Data Unit, with the aim of making innovative projects with high social impact and with a data-driven management to maximize the efficiency of their processes and increase their results.

Telefónica is an important player and its impulse is, without a doubt, a call to action for the rest of the economic, political and social actors. Let’s all make the most of this power together but do so responsibly.

Don’t miss out on a single post. Subscribe to LUCA Data Speaks.

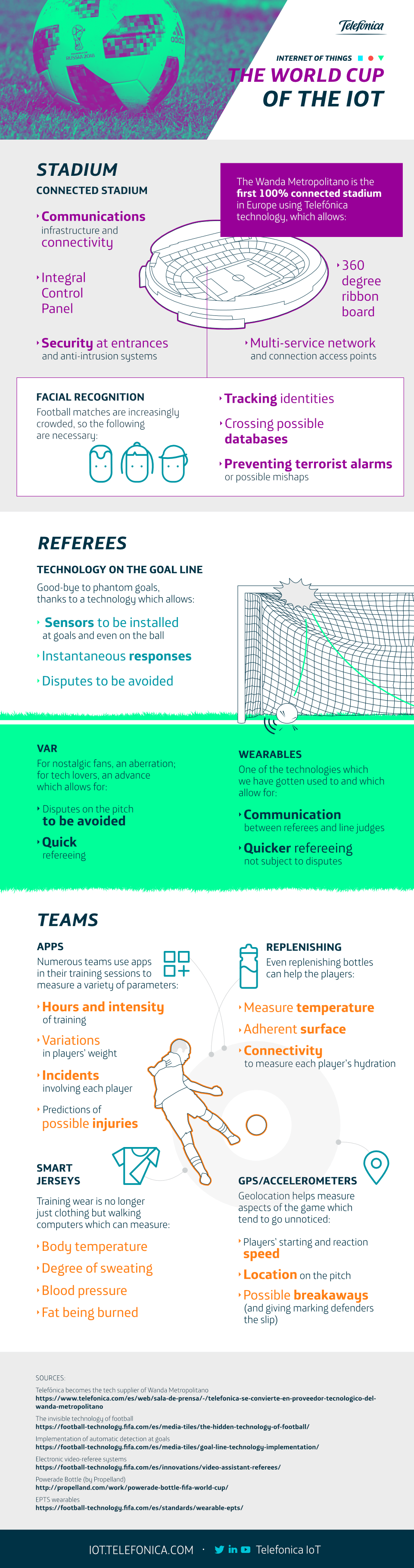

Recently, MacOS included a signature in its integrated antivirus, intended to detect a binary for Windows; but, does this detection make sense? We could think it does, as a reaction to the fact that in February 2019 Trend Micro discovered malware created in .NET for Mac. It was executed by the implementation of Mono, included in the malware itself to read its own code. Ok, but now seriously, does it make sense?

It might make sense to occasionally include a very particular detection that has been disseminated through the media, but in general the long-term strategy of this antivirus is not so clear, although it is intended to detect “known” malware. The fight that MacOS as a whole has against malware is an absolute nonsense. They moved from a categorically deny during the early years of the 21st century to a slight acceptance for finally, since 2009, lightly fight malware. However, since then it has not evolved so much.

Let’s continue with the detection of the Windows executable: the malware was detected in February, which means that it had been working for some time. Trend Micro discovered it and the media made it public, bringing down their reputation. On 19 April, Apple included its signature in XProtect. It is an unacceptable reaction time. On top of all this, it was the first XProtect signature update during all 2019. Is it possible that the malware dissemination was related to the signature inclusion? What is the priority level given to user’s security then? Do we know how much malware is detected by XProtect and how often this seldom-mentioned functionality is updated? Are Gatekeeper and XProtect a way in general to spare their blushes or are they really intended to help mitigate potential infections in MacOS?

What is what

This issue about malware in MacOS is a cyclical, recurrent (and sometimes bored) subject. However, for those who are starting out in security, it is necessary to remind them how dangerous are certain myths that last over time because there are still big “deniers”.

XProtect is a basic signature-based malware detection system that was introduced in September 2009. It constitutes a first approach to an antivirus integrated into MacOS, and it is so rudimentary that when it was launched it was just capable of identifying two families that used to attack Apple operating system and only analyzed files downloaded from Safari, iChat, Mail and now Messages (leaving out well-known browsers for MacOS such as Chrome or Firefox). Currently, XProtect has some more signatures that may be clearly found (malware name and detection pattern) in this path:

/System/Library/CoreServices/XProtect.bundle/Contents/Resources/

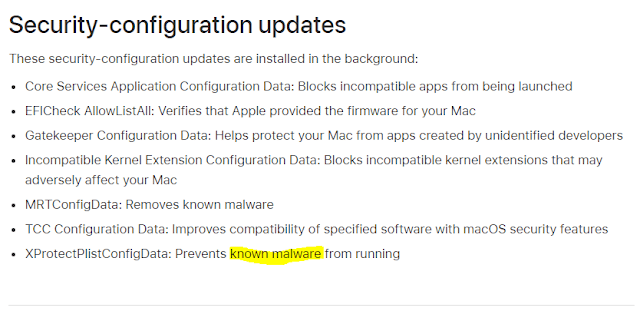

XProtect contains signatures on the one hand, and Yara rules on the other hand (it is defined by XProtect.plist and Xprotect.yara on that directory), and with both systems malware is detected and defined. GateKeeper is supported by both; it monitors and sends it them. The list XProtect.plist is open. Number 3 from the URL refers to Mountain Lion. When 2 is modified, Lion signature file may be viewed, and 1 corresponds to Snow Leopard. Apple does not seem keen to talk too much about it. site:support.apple.com xprotect on Google delivers little results.

GateKeeper has little to do with malware or antivirus, as sometimes it is said. GateKeeper is a system in place to check that downloaded apps are signed by a known ID. To develop for Apple and publish on App Store, the developer must get (and pay) an ID to sign their programs, a kind of certificate. According to Apple, “The Developer ID allows Gatekeeper to block apps created by malware developers and verify that apps haven’t been tampered with since they were signed. If an app was developed by an unknown developer—one with no Developer ID—or tampered with, Gatekeeper can block the app from being installed”. Therefore, Gatekeeper is far from being an antimalware. Rather, it is an apps’ integrity, source and authorship controller that, in case it detects something untrustworthy, it will send it to XProtect and keep it in quarantine if it comes from a suspicious site.

Moreover, there is also MRT for MacOS. It’s its Malware Removal Tool, very close to the Malicious Software Removal Tool for Windows. It is used to reactively remove malware which was already installed, and it can be only executed on system start-up. As if it were not enough, to perform disinfection it trusts very specific and common infection paths, so little can be done.

Why all this does not seem to work too well

“OSX.CrossRider.A”,”MACOS.6175e25″,”MACOS.d1e06b8″,”OSX.28a9883″,”OSX.Bundlore.D”,

“OSX.ParticleSmasher.A”,”OSX.HiddenLotus.A”,”OSX.Mughthesec.B”,”OSX.HMining.D”,

“OSX.Bundlore.B”,”OSX.AceInstaller.B”,”OSX.AdLoad.B.2″,”OSX.AdLoad.B.1″,”OSX.AdLoad.A”,

“OSX.Mughthesec.A”,”OSX.Leverage.A”,”OSX.ATG15.B”,”OSX.Genieo.G”,”OSX.Genieo.G.1″,

“OSX.Proton.B”,”OSX.Dok.B”,”OSX.Dok.A”,”OSX.Bundlore.A”,”OSX.Findzip.A”,”OSX.Proton.A”,

“OSX.XAgent.A”,”OSX.iKitten.A”,”OSX.HMining.C”,”OSX.HMining.B”,”OSX.Netwire.A”,

“OSX.Bundlore.B”,”OSX.Eleanor.A”,”OSX.HMining.A”,”OSX.Trovi.A”,”OSX.Hmining.A”,

“OSX.Bundlore.A”,”OSX.Genieo.E”,”OSX.ExtensionsInstaller.A”,”OSX.InstallCore.A”,

“OSX.KeRanger.A”,”OSX.GenieoDropper.A”,”OSX.XcodeGhost.A”,”OSX.Genieo.D”,”OSX.Genieo.C”,

“OSX.Genieo.B”,”OSX.Vindinstaller.A”,”OSX.OpinionSpy.B”,”OSX.Genieo.A”,”OSX.InstallImitator.C”,

“OSX.InstallImitator.B”,”OSX.InstallImitator.A”,”OSX.VSearch.A”,”OSX.Machook.A”,”OSX.Machook.B”,

“OSX.iWorm.A”,”OSX.iWorm.B/C”,”OSX.NetWeird.ii”,”OSX.NetWeird.i”,”OSX.GetShell.A”,

“OSX.LaoShu.A”,”OSX.Abk.A”,”OSX.CoinThief.A”,”OSX.CoinThief.B”,”OSX.CoinThief.C”,

“OSX.RSPlug.A”,”OSX.Iservice.A/B”,”OSX.HellRTS.A”,”OSX.OpinionSpy”,”OSX.MacDefender.A”,

“OSX.MacDefender.B”,”OSX.QHostWB.A”,”OSX.Revir.A”,”OSX.Revir.ii”,”OSX.Flashback.A”,

“OSX.Flashback.B”,”OSX.Flashback.C”,”OSX.DevilRobber.A”,”OSX.DevilRobber.B”,

“OSX.FileSteal.ii”,”OSX.FileSteal.i”,”OSX.Mdropper.i”,”OSX.FkCodec.i”,”OSX.MaControl.i”,

“OSX.Revir.iii”,”OSX.Revir.iv”,”OSX.SMSSend.i”,”OSX.SMSSend.ii”,”OSX.eicar.com.i”,

“OSX.AdPlugin.i”,”OSX.AdPlugin2.i”,”OSX.Leverage.a”,”OSX.Prxl.2″

Including Eicar and the first XProtect samples of September 2009 (OSX.RSPlug.A, OSX.Iservice).

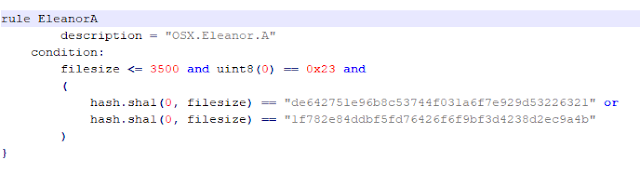

Within this rule, the file is expected to be lower than 3500 bytes (the hash filesize from the example is low, barely 2k) to estimate the hash and this way detect them. Any downloaded file lower than that filesize will be compared to a few hashes, well-known since 2016. Firstly, it discriminates by filesize, and then it detects hash, both variables of little relevance. With the same size structure and hash, we are able to identify 42 of the 92 XProtect’s Yara rules that discriminate by filesize and then trust in hashes to detect malware.

They don’t only rely on hash. XProtect’s Yara rules also use significant strings to detect malware, and add the filesize at the end as a key condition to detect it.

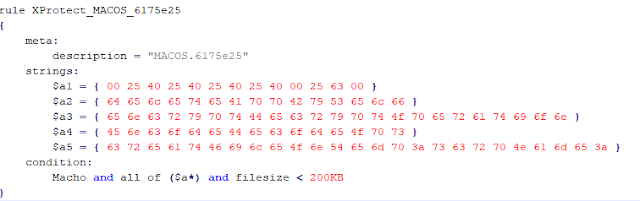

According to this rule, the malware must be a Macho one, contain all the described strings and be lower than 200kb. If it includes all the strings but is higher than 200k, the condition is not matched and would not be detected. Using filesize within Yara rules is not strange or wrong in essence, but in these situations and as a condition for a protection system (not for “hunting”), it does not seem very strong.

And with this discriminatory filesize formula, we are able to find 27 (1/3) of the detections that would be avoided by just modifying the filesize. Remember that 42 of them (almost 1/2) would do it, besides, by tampering a single bit of the file. And all this just with 92 signatures in the “database” and only analyzing those programs from very specific channels (Safari, Mail, iChat and Messages). If we wanted to split hairs, we could mention that SHA1 is already considered obsolete to estimate the hash, but it does not matter too much in this context.

Conclusions

XProtect is not intended to compete against any antivirus, that’s the truth, and is designed to detect known malware. That said, “known malware” is not the same as “known sample”. It should cover at least families and not specific files. We should not expect a lot from it, but it must be seen as a first and very thin protection line against threats. However, we think that, even so, it would not accomplish its task. Rules use hashes to detect, they are limited, and malware definitions are always integrated long after the malware has been disseminated through the media. Anybody could claim that maybe these few signatures cover most of the known malware for MacOS, but even if it is not true, its response capability and detection formula paint an unflattering picture of the system in general. Therefore, we cannot expect a real protection, not even reactive, from XProtect. What may be expected then from this MacOS system? Purely and simply making some users feel secure by displaying a reassuring message on their systems in “ideal infection conditions”.

In their favor, it must be said that at least Apple is not Android (with a detection system as Play Protect, that is ineffective, but at least can be justified) but above all because if at least all users strictly download from Apple Store, there are some guarantees. Unlike Google Play and although its store is not free from malware, Apple Store is quite secure, as iOS and its applications are.

So now the eternal question that deniers like so much. Do you need an antimalware in your MacOS? We could answer yes, we do, but not XProtect. Do not feed the fire, but nor the myths.

Sergio de los Santos

Innovation and Labs (ElevenPaths)

[email protected]

@ssantosv

In the first part of this article we explained how Bayesian inference works. According to Norman Fenton, author of Risk Assessment and Decision Analysis with Bayesian Networks: Bayes’ theorem is adaptive and flexible because it allows us to revise and change our predictions and diagnoses in light of new data and information. In this way if we hold a strong prior belief that some hypothesis is true and then accumulate a sufficient amount of empirical data that contradicts or fails to support this, then Bayes’ theorem will favor the alternative hypothesis that better explains the data. In this sense, it is said that Bayes’ Theorem is scientific and rational, since it forces our model to “change its mind”.

The following case studies show the variety of applications of the Bayes’ Theorem to cybersecurity.

Case Study 1: The success of anti-spam

filters

One of the first successful application

cases of Bayesian inference in the field of cybersecurity were Bayesian filters

(or classifiers) in the fight against spam. Determining if a message is

spam (junk mail, S) or ham

(legitimate mail, H) is a traditional

classification problem for which Bayesian inference was especially suitable.

The method is based on studying the probability that a number of words may appear on spam messages compared to legitimate messages. For example, by checking spam and ham history logs the probability that a word (P) may appear on a spam message (S) may be estimated as Pr(P|S).

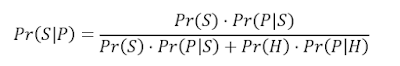

Nevertheless, the probability that it may appear on a legitimate message is Pr(P|H). To calculate the probability that a message will be spam if it includes such Pr(S|P) word we can use once again the useful Bayes’ equation, where Pr(S) is the base rate: the probability that a given e-mail will be spam.

Statistics report that 80% of e-mails that are spread on the Internet are spam. Therefore, Pr(S) = 0.80 and Pr(H) = 1 – Pr(S) = 0.20. Typically, a threshold for Pr(S|P) is chosen, for instance 0.95. Depending on the P word included in the filter, a higher or lower probability compared to the threshold will be obtained, and consequently the message will be classified as spam or as ham.

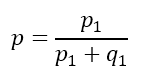

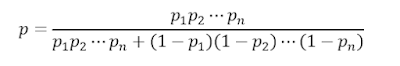

A common simplification consists in assuming the same probability that the one assumed for spam and ham: Pr(S) = Pr(H) = 0.50. Moreover, if we change the notation to represent p = Pr(S|P), p1 = Pr(P|S) and q1 = Pr(P|H), the previous formula is as follows:

But of course, trusting a single world to determine if a message is spam or ham may lend itself to a high number of false positives. For this reason, many other words are usually included in what is commonly known as Naive Bayes classifier. The term “naive” comes from the assumption that searched words are independent, which constitutes an idealization of natural languages. The probability that a message is spam when containing these n words may be calculated as follows:

So next time you open your e-mail inbox and this is free from spam, you must thank Mr. Bayes (and Paul Graham as well). If you wish to examine the source code of a successful anti-spam filter based on Naive Bayes classifiers, take a look at SpamAssassin.

Case Study 2: Malware

detection

Of course, these classifiers may be applied not only to spam detection, but

also to other type of threats. For instance, over last years, Bayesian inference-based malware detection solutions

have gained in popularity:

Case Study 3: Bayesian Networks

Naive Bayesian Classification assumes that studied characteristics are

conditionally independent. In spite of its roaring success classifying spam,

malware, malicious packets, etc. the

truth is that in more realistic models these characteristics are mutually

interdependent. To achieve that conditional dependence, Bayesian networks

were developed, which are capable of improving the efficiency of rule-based

detection systems ꟷmalware, intrusions, etc. Bayesian networks are a powerful type of machine learning for helping

decrease the false positive rate of these models.

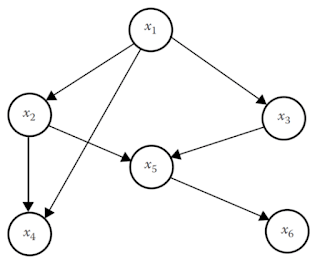

A Bayesian network of nodes (or vertices) that represent random variables, and arcs (edges) that represent the strength of dependence between the variables by using conditional probability. Each node calculates the posterior probability if conditions of parent nodes are true. For example, in the following figure you can see a simple Bayesian network:

And here you have the probability of the whole network:

Pr(x1,x2,x3,x4,x5,x6) = Pr(x6|x5)Pr(x5|x3,x2)Pr(x4|x2,x1)Pr(x3|x1)Pr(x2|x1)Pr(x1)

The greatest challenges for Bayesian networks are to learn the structure of this probability network and train the network, once known. The authors of Data Mining and Machine Learning in Cybersecurity present several examples of applications of Bayesian networks to cybersecurity, as the following one:

In this network configuration, a file server ꟷhost 1ꟷ provides several services: File Transfer Protocol (FTP), Secure Shell (SSH), and Remote Shell (RSH) services. The firewall allows FTP, SSH and ANDRSH Traffic from a user workstation (host0) to the server 1 (host1). The two numbers in parenthesis show origin and destination host. The example addresses four common vulnerabilities: sshd buffer overflow (sshd_bof), ftp_rhosts, rsh login (rsh) and setuid local buffer overflow (Local_bof). The attack path may be explained by using node sequences. For example, an attack path may be presented as ftp_rhosts (0, 1) → rsh (0, 1) → Local_bof (1, 1). Values of conditional probability for each variable are shown in the network graphic. For instance, the Local_bof variable has a conditional probability of overflow or no overflow in user 1 with the combinational values of its parents: rsh and sshd_bof. As it may be seen:

Pr(Local_bof(1,1) = Yes|rsh(0,1) = Yes,sshd_bof = Yes) = 1,

Pr(Local_bof (1, 1) = No|rsh(0, 1) = No,sshd_bof(0, 1) = No) = 1.

By using Bayesian networks, human experts can easily understand the structure of the network as well as the underlying relationship between the attributes among data sets. Moreover, they can modify and improve the model.

Case Study 4: The CISO against

a massive data breach

In How to Measure Anything in

Cybersecurity Risk, the authors present an example of Bayesian inference

applied by a CISO. In the scenario raised, the

CEO of a large organization calls his CISO because he is worried about the

publication of an attack against other organization from their sector, what is

the probability that they may suffer a similar cyberattack?

The CISO gets on with it. What can he do to estimate the probability of suffering an attack, apart from checking the base rate (occurrence of attacks against similar companies in a given year)? He decides that performing a pentest could provide a good evidence on the possibility that there is a remotely exploitable vulnerability, that in turn would influence on the probability of suffering such attack. Based on his large experience and skills, he estimates the following probabilities:

These prior probabilities are his previous knowledge. Equipped with all them as well as the Bayes’ equation, now he can calculate the following probabilities, among others:

It is clear how pentest results are critical to estimate the remaining probabilities, given that Pr(A|T) > Pr(A) > Pr(A|¬T). If a condition increases the prior probability, then its opposite should reduce it.

Of course, the CISO’s real work life is much more complex. This simple example provides us a glimmer of how Bayesian inference may be applied to modify judgements according to evidences accumulated in an attempt to reduce uncertainty.

Beyond classifiers: Bayesians’ everyday life in cibersecurity

Does this mean that since now you need to carry an Excel sheet everywhere in order to estimate prior and posterior probabilities, likelihoods, etc.? Fortunately, it doesn’t. The most important aspect of Bayes’ theorem is the concept behind Bayes’ view: getting progressively closer to the truth by constantly updating our belief in proportion to the weight of evidence. Bayes reminds us how necessary it is for you to feel comfortable with probability and uncertainty.

A Bayesian cybersecurity practitioner:

Riccardo Rebonato, author of Plight of the Fortune Tellers: Why We Need to Manage Financial Risk Differently, asserts:

According to the Bayesian view of the world, we always start from some prior belief about the problem at hand. We then acquire new evidence. If we are Bayesians, we neither accept in full this new piece information, nor do we stick to our prior belief as if nothing had happened. Instead, we modify our initial views to a degree commensurate with the weight and reliability both of the evidence and of our prior belief.

First part of the article:

» How to forecast the future and reduce uncertainty thanks to Bayesian inference (I).

DeepMind has partnered with Moorfields Eye Hospital to develop a diagnostic technology to bring to market, which can help to detect the early signs of sight-threatening conditions, which, through early detection, can usually be treated and often reversed.

As is already known, Artificial Intelligence is already being used within this field with eye specialists using Optimal Coherence Tomography (OCT scans) to aid them in their diagnoses on a day-to-day basis. However, these scans have proven to have their limitations.

These 3D scans provide a detailed image of the back of the eye. However, this requires highly trained, expert analysis to interpret and to make accurate diagnoses, which is in short supply and therefore, this is a time-consuming process. This can cause major delays in treatment which in some cases can be sight-threatening, if, for instance a bleed was to appear at the back of the eye and was untreated due to excess time waiting for OCT scan results.

According to the official report, the idea of this new technology is that it will analyse the ‘basic’ OCT scan extremely efficiently (taking just 30 seconds in one demonstration) and will identify from the images a wide range of eye diseases along with recommendations of how they should be treated and the urgency of each individual patient’s situation.

This is solving an issue long discussed within this sector; the ‘black box problem’. This is because for the first time, the AI is providing context to the professionals to aid in their final decision; it not only presents the findings but explains how it has arrived at this diagnosis and recommendation. This is in turn leaving room for the specialist to scrutinise the information which is provided to an appropriate level, so as to ensure the best treatment plan for each specific patient is reached. This is aided by the fact that the technology provides a confidence level of its findings in the form of a percentage which will determine the degree to which the specialist will need to question the result.

The technology uses two neural networks with an easily interpretable representation between them which has been split up into 5 distinct steps.

It starts with the raw OCT scan with which the segmentation network uses a 3D U-Net architecture to translate the scan into a detailed tissue map, which includes 15 classes of detail including anatomy and pathology having been trained with 877 clinical OCT scans.

Next the classification network analyses the tissue map and as a primary outcome provides one of 4 referral recommendations currently in use at Moorfields Eye Hospital:

For the training of this classification network, DeepMind collated 14,884 OCT scans of 7621 patients sent to the hospital with symptoms suggestive of macular pathology (the macular being the central region of the retina at the posterior pole of the eye). The final step as previously mentioned includes providing possible diagnoses with a percentage confidence level allowing appropriate scrutiny of the result to take place when necessary.

A major challenge in the use of OCT image segmentation (step 2 of 5 mentioned above) is the presence of ambiguous regions where the true tissue type cannot be deduced from the image meaning that there are multiple plausible interpretations which exist.

To overcome this, multiple instances of the segmentation network have been trained with each network instance creating a fully detailed segmentation map allowing multiple hypothesis to be given. As a result, doctors can analyse the evidence and select the most applicable hypothesis for each individual patient. Interestingly, the report states that in areas with clear image structures, these network instances may agree and provide similar results, and that videos can even be produced showing these results with further clarity.

Achieving ‘expert performance on referral decisions’ is the main outcome which is hoped for with this project as an incorrect decision, in some cases, could lead to rapid sight-loss for a patient.

Within the report made about this project, DeepMind has stated that to optimise quality, first they needed to define what a Gold Standard of service is.

“This used information not available at the first patient visit and OCT scan, by examining the patient clinical records to determine the final diagnosis and optimal referral pathway in the light of that (subsequently obtained) information. Such a gold standard can only be obtained retrospectively”

Not including the people used in the training data set, Gold Standard labels were acquired for 997 patients and these were the patients which were used for testing the framework. Each patient received a referral suggestion from the network as well as independent referral suggestions from 8 specialists, 4 of whom were retina specialists and 4 of whom were optometrists trained in the retina.

Each of the 8 specialists provided 2 recommendations, one simply using the OCT scan and one using the OCT scan as well as the fundus imaging and clinical notes and these were given during separate sessions spaced at least two weeks apart.

The performance of the framework matched the referrals of 2 of the retinal specialists and exceeded those of the other 6 specialists when they were simply using the OCT imaging. When they had full access to notes and fundus images their performance improved but this time the framework matched the performance of 5 of the specialists but still continued to outperform the remaining 3. Overall, the framework performed very well not making any serious clinical errors.

As I have previously stated, the framework uses an ensemble of 5 segmentation model instances, but it also uses 5 classification model instances, and this is clinically proven to lead to more accurate results. In the testing process, it was found that when deriving a score for our framework and the experts as a weighted average of all wrong diagnoses, the framework achieved a lower average penalty point score than any of the experts.

What is exciting about this two-stage framework is how the second network (classification network) is independent of the segmentation network. Therefore, to use it on another device, only the segmentation stage would need to be retrained so that the system knows how each tissue type appears on the scan image.

This has been tested on different devices which perform OCT scans, including Spectralis, from Heidelberg Engineering, which is the second most used device type at Moorfields Eye Hospital. It achieved an erroneous referral suggestion in only 4 of the 116 cases tested, similar to the 5.5% error rate of device 1.

A first step however in getting this technology to a more widespread audience, is its application in all Moorfields Hospitals in the UK for the first 5 years if and when it is launched, free of charge! As well as this, due to the fact it can be applied to a wider range of devices, it will be much cheaper for other organisations to apply the technology to their existing devices rather than having to purchase additional specialist equipment.

In all, this could be a giant leap for many countries around the world, hugely increasing the number of people who could potentially benefit from this innovative technology rather than limiting itself to one device and therefore limiting who can use it.

Overall, according to DeepMind, the initial 14 months of research and development have been very successful, and this technology is by no means ready to be launched into the marketplace. However, with more rigorous testing and technological developments, before long it is certain that we will be seeing this technology implemented nationally and possibly even internationally. We hope that with this framework as a basis, in the future, others will be able to build on this work, branching out into new areas of this sector now that the ‘Black Box’ problem has been identified and somewhat overcome. Additionally, looking outside the box, many have suggested that this technology could even be useful for training purposes as people would be able to use the technology to learn how to interpret images of the eye and how and where to look for aspects within the image creating cause for concern.

It is said that this could be a revolutionary step forward in this field and that much like 5G will allow people in rural áreas around the world to gain Access to healthcare specialists, this AI technology will provide the fastes and most accurate diagnoses no matter where someone is situated in the world.

Don’t miss out on a single post. Subscribe to LUCA Data Speaks.

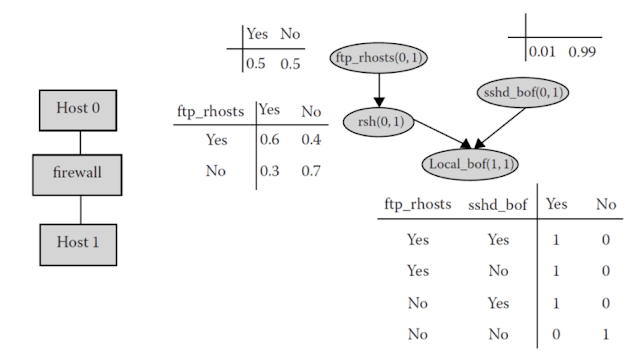

We have detected a malware sent to some email accounts belonging to a Vietnam government domain. This email is written in Vietnamese and is dated March 13th, 2019. It seems to come from an account inside the organization (gov.vn), maybe someone sending it to a security operator, because of resulting suspicious. The attached file resulted in a very interesting infection system. It uses a combination of techniques never seen before, making us think about a very targeted campaign, using interesting resources to specifically infect Vietnam government.

The global view of the threat schema is the following:

Although it may look typical, the schema hides some very smart techniques to avoid detection and fool the system.

Inside the ZIP there is no actual file. Instead, we can find a link file with .lnk extension that simulates a document icon. This has been used before by attackers, but it is not a very popular tool. The actual payload resides in the Target property of the link file, where the LNK points to. The target contains MS-DOS obfuscated code to compose itself.

The result (using a technique called “carving”) will be a PS file, base64 encoded, saved in %TEMP% variable and named s.ps1. DOS obfuscation refers to a technique based in DOS commands (used for BAT programming) that obfuscates itself using loops, environment variables and composing names taking substrings from filenames, directories, etc.

This PowerShell, once executed, will create and run another PowerShell file, that will reside only in memory and that, again, will run a WScript Shell. The Script will create again other three files:

1. A decoy DOC file, making the victim think that an actual doc file has been opened.

2. A legitimate tool to install .NET assembled files. This Will be used to bypass SmartSCreen and AppLocker protection, since the actual payload will be a parameter of this legitimate file.

3. A DLL file, created in .NET that contains the actual malicious payload.

It hides even more surprises to stay stealth. All technical details in the following report.

This malware uses some very interesting techniques that, if not new, are not common, and even less used altogether in a single attack.

We are still working in the attribution, if possible.

All around the world, a popular pastime is the consumption of beer, and we are beginning to see the increasing use of AI and machine learning in various aspects of the beer industry, from production, to marketing and sales all the way, in some cases (as I will mention) to the final service.

We begin with a case where AI systems are being used to collect data and improve the product specifically for its consumers specific needs and wants.

With AI technology increasingly being used

in packaging, and in some cases with important marketing decisions, a company called IntelligentX has revolutionised the use of AI in this sector by taking it a step further

IntelligentX is the world’s first company using machine learning

and AI algorithms to help adjust the recipes of (as of this moment) its 4 main

beers.

To keep up to date with LUCA visit our website, subscribe to LUCA Data Speaks or follow us on Twitter, LinkedIn or YouTube .

Imagine that you come back home from San Francisco, just arrived from the RSA Conference. You are unpacking your suitcase, open the drawer where you store your underwear and… what do you discover? A piece of underwear that is not yours! Naturally, you ask yourself: How probable is that my partner is cheating on me? Bayes’ theorem to the rescue!

The concept behind the Bayes’ theorem is surprisingly straightforward:

By updating our previous beliefs with objective new information, we get a new improved belief

We could formulate this almost philosophical concept with simple math as follows:

New improved belief = Previous beliefs x New objective data

Bayesian inference reminds you that new evidences force you to check out your previous beliefs. Mathematicians quickly coined a term for each element of this method of reasoning:

Naturally, if you apply the inference several times in a row, the new prior probability will get the value of the old posterior probability. Let’s see how Bayesian inference works through a simple example from the book Investing: The Last Liberal Art.

Bayesian inference in action

We have just ended

several dice board games. While we are storing all pieces in their box, I roll

a dice and cover it with my hand. “What is the likelihood of having a 6?” ꟷI

ask you. “Easy”, ꟷyou answerꟷ “1/6”.

I check carefully the number under my hand and say: “It is an even number. What is the likelihood of still having a 6?”. Then, you will update your previous hypothesis thanks to the new information provided, so you will answer that the new probability is 1/3. It has increased.

But I give you more information: “It is not 4”. What is the probability now that there is a 6? Once again, you need to update your last hypothesis with the new information provided, and you will reach the conclusion that the new probability is 1/2, it has increased again. Congrats!! You have just carried out a Bayesian inference analysis!! Each new objective data has forced you to check out your original probability.

Let’s analyze, armed with this formula, your partner’s supposed unfaithfulness.

How to apply Bayesian inference to discover if your partner is unfaithful to you

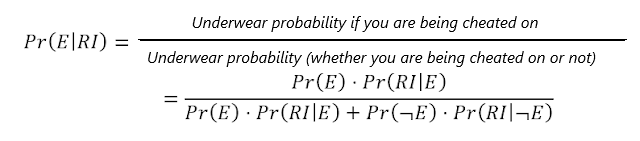

Turning to the initial question: Is my partner cheating on me? The evidence is that you have found strange underwear in your drawer (RI); the hypothesis is that you are interested to evaluate the probability that your partner is unfaithful to you (E). Bayes’ theorem may clarify this issue, provided that you know (or are ready to estimate) three quantities:

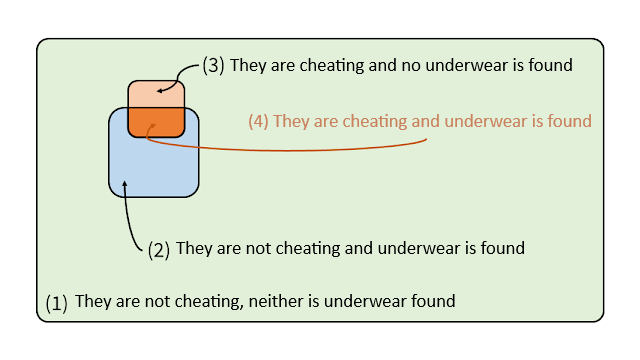

Assuming a good work when estimating these values, now you only need to apply the Bayes’ theorem to set the posterior probability. In order to make these calculations easier, let’s assume a group of 1,000 couples ꟷrepresented through the big green rectangle of the following image. It is easy to see that, if 40 out of 1,000 people cheat on their partner, and half of them forget their lover’s underwear in their partner’s drawer, 20 people have forgotten underwear (group 4). Furthermore, out of 960/1,000 people that don’t cheat on their partners, 5% have let underwear in their partner’s drawer by mistake, this is, 48 people (group 2). By adding both figures we have as a result 68 mysterious pieces of underwear that will have appeared spread over couples’ drawers (group 2 + group 4).

Consequently, if you find a strange piece of underwear in your drawer, what is the probability that your partner is cheating on you? It will be the number of pieces of underwear found when couples are unfaithful to their partners (4) divided into the total number of pieces of underwear found, belonging to both unfaithful and faithful partners (2 + 4). There is no need to calculate anything, it jumps out at you that a strange piece of underwear is more likely due to a faithful than to an unfaithful partner. In fact, the exact value of the posterior probability is: Pr(E|RI) = 20/68 ≈ 29%.

We can mathematically collect the quantities from the previous image by following the so-called Bayes’ equation:

By replacing the appropriate numerical values, we obtain once again the probability that your partner is cheating on you: only 29%! How do you get this unexpectedly low result? Because you have started from a low prior probability (base rate) of unfaithfulness. Although your partner’s explanations of how that underwear has got into your drawer are rather unlikely, you started from the premise that your partner was faithful to you, and this weighed heavily on the equation. This is counterintuitive, because… Is not that piece of underwear in your drawer an evidence of your partner’s guilt?

Our System I heuristics, adapted to quick and intuitive judgements, prevent us from reaching better probability conclusions based on the available evidence. In this example, we pay excessive attention to the evidence (strange piece of underwear!) and forget the base rate (only 4% of unfaithfulness). When we let ourselves to be dazzled by new objective data at the expense of previous knowledge, our decisions will be consistently suboptimal.

But you are a Bayesian professional, right? So, you will give your partner the benefit of the doubt. Mind you, you could make a remark and tell your partner not to buy opposite-sex underwear, not to give you underwear, or not to invite a platonic friend to spend a night. Under these conditions, the probability that in the future a strange piece of underwear may appear in your drawer if your partner is faithful to you will be at most 1%, this is Pr(RI|¬E) = 0,01.

What would it happen if a few months later you find again strange underwear in your drawer? How would it change now your certainty belief that your partner is guilty? As a new evidence appears, a Bayesian practitioner will update their initial probability estimation. The posterior probability that your partner was cheating on you the first time (29%) will become the prior probability that your partner is cheating on you this second time. Bayesian practitioners adapt their evaluation of future probability events according to the new evidence. If you reintroduce the new values in the previous formula, Pr(E) = 0,29 y Pr(RI|¬E) = 0,01, the new posterior probability that your partner is being unfaithful will be 95%. Now you have grounds for divorce!

This illustrative example, from The Signal and the Noise: The Art and Science of Prediction, shows that:

In the following part of this article, we will go over several case studies where Bayesian inference is successfully applied to cybersecurity.

Second part of this article:

» How to forecast the future and reduce uncertainty thanks to Bayesian inference (II).

Gonzalo Álvarez Marañón

Innovation and Labs (ElevenPaths)

[email protected]

As of now, driverless car technology is very temperamental, and errors are still far too common to be able to safely rely on them. The eventual aim is to achieve artificial general intelligence where the technology can replicate the human driver without replicating human mistakes.

One major problem is that in theory, machine learning will teach the technology the rules of the road and how to legally drive, but this technology does not have the judgement or the responses of actual human beings. As a result, it doesn´t always take into account what other drivers are doing or the ever-changing environment around it and therefore, AI decision-making is becoming more of an obstacle when it comes to gaining the trust of the public.

Very common occurrences, ranging from safely allowing another vehicle to pass which may involve a lane change, to adapting to varying weather changes are proving to be challenges for various companies within this field. The weather is a particular worry for some, as human beings find driving in harsh conditions difficult at the best of times. We have already seen that the sensors on Google AI cars have been affected by rain as it can affect the LIDAR´s ability to read the road signs which shows just how vulnerable even the most advanced technology can be.

“The idea is to use humans to bridge the gap between simulation and the real world”.

The researchers states that over time, a ‘list’ is compiled of different situations and what the correct and incorrect reactions are in the hope that through machine learning, this AI technology can, over time, improve greatly.