All cyber security professionals now know at least part of what was originally thought to be “just” an attack on SolarWinds, which has just truned out to be one of the most interesting operations of recent years. We will dwell on the more curious details of the incident, but we will also focus on the management of this crisis. What has been done right and what has been done wrong to gauge the maturity of an industry that will suffer more and worse attakcs than this in the future

FireEye raises the alarm on Tuesday 8 December. They have been attacked. But the industry does not blame FireEye for this, but backs them up and supports them in general, their response is exemplary. It has happened to many and it can happen to all of us, so the important thing is how you deal with it and be resilient.

Since attackers have access to sensitive tools internal to their company, FireEye does something for the industry that honours them: they publish the Yara rules necessary to detect whether someone is using those tools stolen from the FireEye offensive team against a company. A fine gesture that is again publicly credited. Not much more is known about the incident and it is still being investigated.

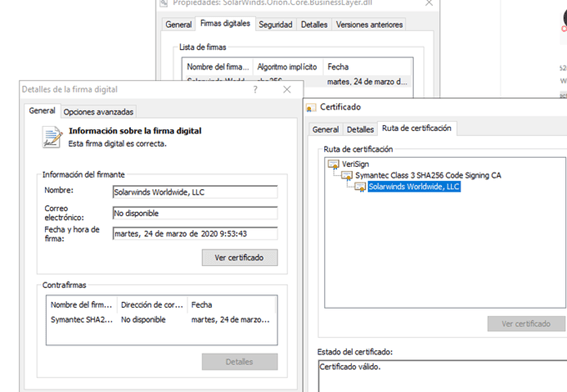

But then everything gets complicated, and in a massive way. The news begins: The US Treasury Department and many other government departments also admit an attack. On the same day, the 13th, FireEye offers a very important detail: the problem lies in the Trojanization of SolarWinds’ Orion software. An upgrade package, signed by SolarWinds itself, included a backdoor. It is estimated that over 18,000 companies use this system. Pandora’s box is opened because of the characteristics of the attack and because it is a software used in many large companies and governments. And since global problems require global and coordinated reactions, this is where something seemed to have gone completely wrong.

Did the Coordination Fail?

The next day, December 14, with the information needed to point at “ground zero” of the attack, the reactive methods still did not work. In particular:

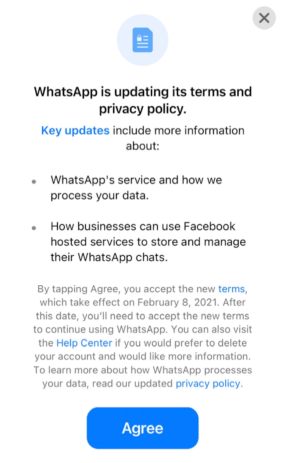

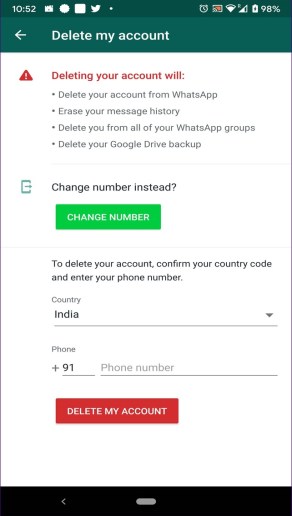

- The trojanized package was still available in the SolarWinds repository even though on the 14th it had been known for at least a week (but most likely longer) that this package was trojanized and had to be removed.

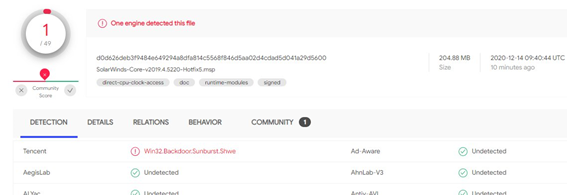

- Antivirus engines were still unable to detect the malware (which has become known as SUNBURST). On that same Monday it was not found in the static signatures of the popular engines.

- The certificate with which the attackers signed the software was still not revoked. Whether they gained access to the private key or not (unknown), that certificate had to be revoked in case the attacker was able to sign other software on behalf of SolarWinds.

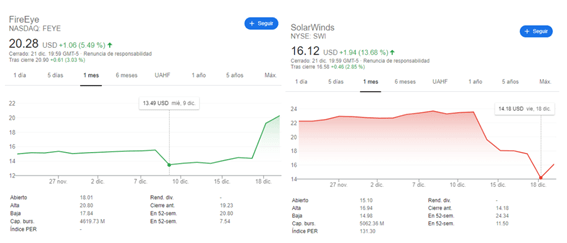

Here we can only guess why this “reactive” element failed. Was SolarWinds late in the attack? Did FireEye publish the details to put pressure on SolarWindws when it was already clear that the attack concealed a much more complex offensive? Of course, the stock market has “punished” both companies differently, if it can be used as a quick method of assessing the market’s reaction to a serious compromise. FireEye has turned out to be the hero. SolarWinds, the bad guy.

However, there have been reactions that have worked, such as Microsoft hijacking the domain under which the whole attack is based (avsavmcloud.com). Which, by the way, was sent from Spain to urlscan.io manually on 8 July. Someone may have noticed something strange. The campaign had been active since March.

The Malware itself and the Community

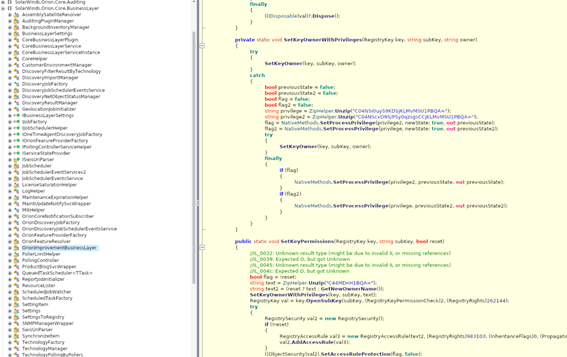

The “good” thing about SUNBURST is that it is created in .NET language, making it relatively easy to decompile and know what the attacker has programmed. And so, the community began to analyse the software from top to bottom and program tools for a better understanding.

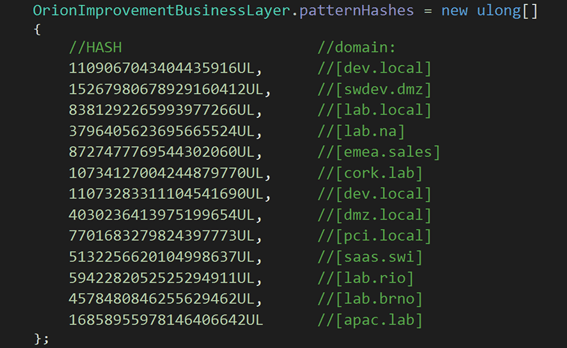

The malware is extremely subtle. It did not start until about two weeks after it was found on the victim. It modified scheduled system tasks to be launched and then returned them to their original state. But one of the most interesting features of the malware is the ability to hide the domains it uses, which required brute force to reveal them (they were hashes). In addition, it contained the hash of other domains that it did not want to infect. But which ones?

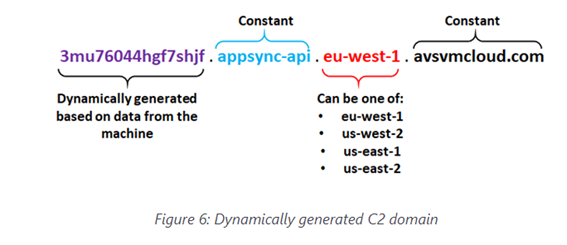

All, most likely, internal to the SolarWinds network, to go unnoticed in its internal network. An indication that the initial victim was SolarWinds and that in order to achieve this, the attackers had to know their victim well. A code was issued to pull out any tool list (their names were also hashed) to find out what the trojan didn’t want to see on the machine. Many of the tools and hashed domains were revealed in record time and it was possible to recognise what these attackers had in mind. Another tool has been published to decrypt the DGA (Domain Generator Algorithm) where it tried to contact the malware. One of the strong points of the algorithm was precisely the DGA, but also its weak point (the top-level domain was always the same).

In the end, the malware ended up composing URLs like this:

- hxxps://3mu76044hgf7shjf[.]appsync-api[.]eu-west-1[.]avsvmcloud[.]com /swip/upd/Orion[.]Wireless[.]xml

Where it “exfiltrated” the information and communicated with the Command and Control. Well thought out from the attacker’s point of view because it goes unnoticed due to its “normality”, but badly thought out from the perspective of persistence

Another very interesting point that seems to have gone unnoticed, is that the attackers seemed to “inflate” during 2019 the trojan module from 500 to 900k, without injecting relevant code but increasing the size of the DLL. In February 2020 they introduced the espionage charge into the same DLL, thus achieving an extra invisibility without raising suspicions due to the increase in size.

Don’t Go Yet, There Is Still More

More recently, it seems that Orion from SolarWinds was not only trojanized with SUNBURST but also with what has come to be called SUPERNOVA. Perhaps another actor also had the possibility to enter the network and deployed a different trojan in the tool. Although we still do not have many details of how it worked, this is the second nightmare that can still be talked about.

Conclusions

We are facing one of the most sophisticated attacks in recent times, which has not only put in check a company that is dedicated to defending other companies, but also governments, major ones like Microsoft and others that we cannot even imagine. They have gone one step further launching a campaign that is almost perfect in its impact and execution. On other occasions (the RSA, Bit9, Operation Aurora…), large companies have been attacked too and also sometimes only as a side effect in order to reach a third party, but on this occasion a step forward has been taken in the discretion, precision and “good work” of the attackers. And all thanks to a single fault, of course: the weakest point they have been able to detect in the supply chain on which major players depend. And yes, SolarWinds seemed a very weak link. On their website they recommended deactivating the antivirus (although this is unfortunately common for certain types of tools) and they have shown to use weak passwords in their operations, in addition to the fact that there are indications that they have been compromised for more than a year… twice

Should we be surprised at such weak links in the cyber security chain on which so much depends? We depend on an admittedly patchy picture in terms of cyber security skills. Asymmetric in response, defence and prevention capabilities, both for victims and attackers… but very democratic in the importance of each piece in the industry. There is no choice but to respond in a coordinated and joint manner to mitigate the risk. It is not difficult to find similarities outside the field of cyber security. In any case, and fortunately, once again, the industry has shown itself to be mature and capable of responding jointly, not only by the community, but also by the major actors. Perhaps this is the positive message we can pull out of a story that still seems to be unfinished.