Throughout the next few weeks, Mobile Connect will be trialled in two EU Member States, establishing proof-of-concept for cross-border authentication to e-Government services. The pilot, launched on November 16, will demonstrate how Mobile Connect can be used to identify an EU-citizen of one Member State in order to gain access to a public service of another. Mobile Connect offers a simple way of achieving pan-European federation of cross-border services for the EU governments compatible with the eIDAS regulation, whilst enabling growth in digital public services nationally.

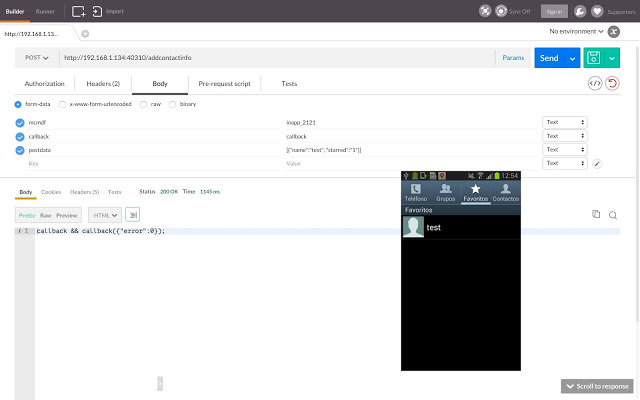

The trial is taking place between Spain Catalunia and Finland, and will enable customers of participating Spanish operators, to log-in to a Finnish eGovernment service, and on the Catalunia side the log-in through a digital identity validator granting access to a complete public services portfolio. The customer experience is the same in both countries: After the customer presses the Mobile Connect button and enters their mobile number on the discover page, a PIN request appears on their mobile phone. By entering the correct PIN, the user’s identity is confirmed and the customer is logged-in to the eGovernment online service.

The pilot is the result of collaboration between organisations seeking to accelerate the uptake of trusted and secure digital authentication in response to the eIDAS Regulation. The Regulation aims to enhance trust in electronic transactions in the EU internal market by providing a common foundation for secure electronic interaction between citizens, businesses and public authorities, thereby increasing the effectiveness of online services in the EU. The GSMA with major operators, Orange Spain, Telefonica, TeliaSonera, and Vodafone Spain are supporting the trial, as well as Gemalto, Mobile World Capital, the Catalonia Regional Government, the Finnish Ministry of Finance and Finnish Population Registration Centre.

Hear from the participants in the trial on their experience with Mobile Connect:

“Finally with Mobile Connect we can create international eID services that are based on real identities, and for those identities we can create a new breed of trust services for a global market.” Joni Rapanen, TeliaSonera.

“We in the Ministry of Finance are very satisfied with this successful project. Our role was limited compared with the participants who planned the actual trial, but the results are very important to us when we are building a national trusted network for e-identification.“ Mr Olli-Pekka Rissanen, Special Adviser, Ministry of Finance.

“Orange Mobile Connect solution meets the needs of our customers for a secured journey and also paves the way for a rapid take-off of eIDAS services” Alicia Calvo, Innovation Director, Orange Spain.

“Mobile Connect is a key component of Telefonica’s security services. It has greatly expanded the identity and privacy solutions we offer to our customers” José Luis Gilpérez, Defense and Security Director, Telefónica.

“For Vodafone, it is important to provide to our Customers confidence and simplicity when using digital services. Mobile Connect will be a key enabler of the Customers Digital Journey” Ibo Sanz, mCommerce Director, Vodafone Spain.

“The identification and trust services for electronic transactions in the internal market aligned with eIDAS regulation, is a milestone for a Government of Catalonia to provide a confident environment to enable secure and seamless electronic interactions or transactions between European businesses, citizens and public authorities. In this regard, this experience, is focused on this European government’s spirit of collaboration” – Jordi Puigneró – General Director for Telecommunications and ICT at Government of Catalonia.

Oscar Pallarols, Smart Living Director at Mobile World Capital Barcelona. .

The trial occurs just weeks after the EU’s recent adoption of the implementation rules of the eIDAS Regulation, which makes the EU the first and only region in the world to have a legal framework for safe cross-border access to services and online interactions between businesses, citizens and public authorities.

The Regulation is part of the European Commission’s push towards the Digital Single Market, and is designed to enable citizens to carry out secure cross-border electronic transactions. For example, enrolment in a foreign university, filing of multiple tax returns, access to electronic medical records or authorisation of a doctor to access these on one’s behalf. It will also enable citizens moving or relocating to another member state to manage registration and other administration online with the same legal certainty as they currently have with traditional paper-based processes.

Mobile Connect’s technical architecture follows secure user authentication requirements provisioned by the eIDAS Regulation, and its technical specifications of implementation – and is the first private-sector cross-border public service authentication solution to be compatible with it. As such, the pilot will test how eIDAS cross border authentication works and reveal any practical challenges in implementing the solution.

The solution is ideally placed to address both service providers’ needs acting as a primary log-in for websites, apps, and other online services and consumers’ demands for straightforward and secure authentication and identification. Mobile Connect can help government agencies and other service providers increase usage of their online services, improving efficiency, enriching the end-user experience and increasing engagement. With the demand for secure and convenient authentication for digital services at an all-time high, this pilot further illustrates the market readiness of Mobile Connect. To find out more email the team at [email protected]

Source: GSMA

Original post Mobile Connect makes headway with launch of cross-border pilot by GSMA.